The 68th session of the “Adventus Amicorum” seminar series, organized by the Institute of Area Studies, Peking University (PKUIAS), was held on November 13, 2025. The seminar, titled “The Return of the Repressed: The Colonial History of the EU’s Geopolitical Turn”, was delivered by Prof. Peo Hansen from Linköping University, Sweden. The event was moderated by Zhang Yongle, deputy director of PKUIAS and tenured associate professor at the School of Law, PKU. The discussants included Zan Tao, deputy director of PKUIAS and professor at the Department of History; You Mi, a professor at the Art and Economies, Kassel University; Duan Demin, a tenured associate professor at the School of Governance, PKU; and Liu Haifang, an associate professor at the School of International Studies, Peking University.

Hansen commenced his address by emphasizing the idea of the “long twentieth century,” arguing that many conflicts and geopolitical fissures rooted in the aftermath of the First World War remain unresolved. He suggested that this historical continuity explains why the European Union continues to confront challenges that echo earlier crises. One example is the EU’s current approach to the war in Ukraine, which centers on achieving Russia’s military defeat and long-term strategic weakening. According to Hansen, this strategy reproduces twentieth-century geopolitical thinking and amounts to a doubling down on policies that have already failed. Not only is such an approach unrealistic, but it also carries the grave risk of escalating the conflict into a wider war.

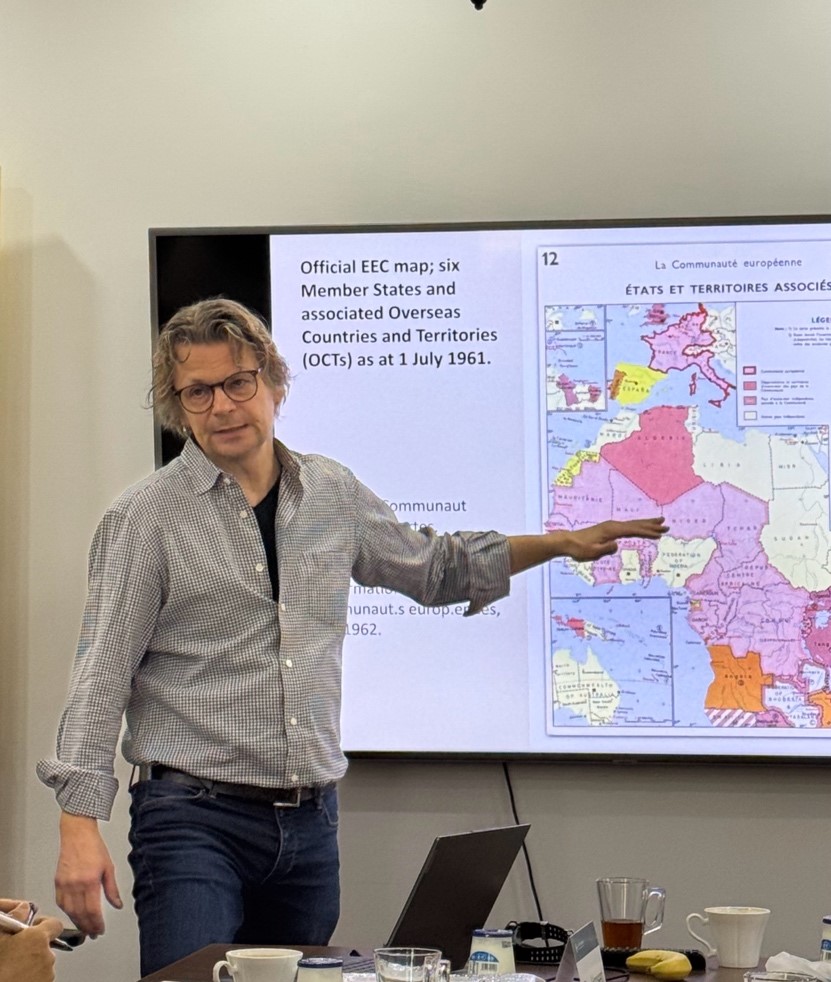

Hansen traced the deep entanglement between European integration and Europe’s colonial past. Drawing on archival records and cartographic evidence, Hansen argued that early plans for maintaining control over African colonies and extracting their resources were integral to the formation of the European Economic Community. This logic informed the concept of “Eurafrica,” in which Africa was imagined as essential to Europe’s unity and strength. He noted that such externalized foundations of internal cohesion continue to shape EU discourse today, particularly in the framing of Africa as the “geopolitical priority.”

Turning to contemporary debates on “strategic autonomy” and “speaking with one voice,” Hansen highlighted the long-standing logic of great-power dominance embedded in these discourses. He recalled that since the post-Napoleonic “Concert of Europe”, small states have repeatedly been portrayed as obstacles to effective decision-making. Current proposals to dilute member-state veto power in the name of efficiency, he argued, represent a modern iteration of imperial governance. Efforts of this kind risk deepening internal fractures, while exposing the power politics that often underlie appeals to “common interests” and “shared values.”

Hansen placed particular emphasis on the period of détente in the 1970s and 1980s, describing it as a valuable yet underappreciated historical resource. The Helsinki Final Act (1975) and Chancellor Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik (German: “Eastern Policy”), he explained, embodied a realist attempt to transcend geopolitical confrontation through coexistence and non-coercive diplomacy. During these years, several European states interpreted their relative decline not as a crisis to be overcome but as an opening for new forms of cooperation. Neutral states in Western Europe and non-aligned countries, particularly Yugoslavia, played crucial roles in shaping this cooperative configuration.

During the discussion session, participating faculty and students raised questions concerning the contradictions in Europe’s geopolitical turn, the evolution of Europe-Africa relations, and the broader implications for regional integration and global order. Hansen stressed that the EU’s zero-sum posture toward China in Africa is both counterproductive and misguided, and that Europe has yet to fully abandon its colonial habit of treating Africa as a sphere of influence. He also underscored that in the history of European integration, durable cohesion emerged primarily from non-coercive, consensus-based diplomacy rather than from enforced unity. By contrast, today’s trend toward greater centralization within the EU is exacerbating developmental imbalances and may ultimately hinder, rather than advance, genuine integration.